Claude Haiku vs. Sonnet: Orchestrating AI for Max

The End of the “One Model” Era: An Analysis of Claude Haiku vs. Sonnet

The artificial intelligence development scene has changed quickly, leaving developers, writers, and business leaders confused. For the past year, choosing an AI model was simple. If you wanted intelligence, you paid a premium for a “smart” model (like Claude Sonnet or Opus); if you wanted speed and low cost, you settled for a “dumb” one (Haiku). That trade-off no longer holds.

With Claude Haiku 4.5’s release, the “middle class” of AI models has effectively disappeared. We now have a budget model that outperforms state-of-the-art flagship models from just five months ago. This is more than a spec sheet update; it is a fundamental shift in the economics of automation.

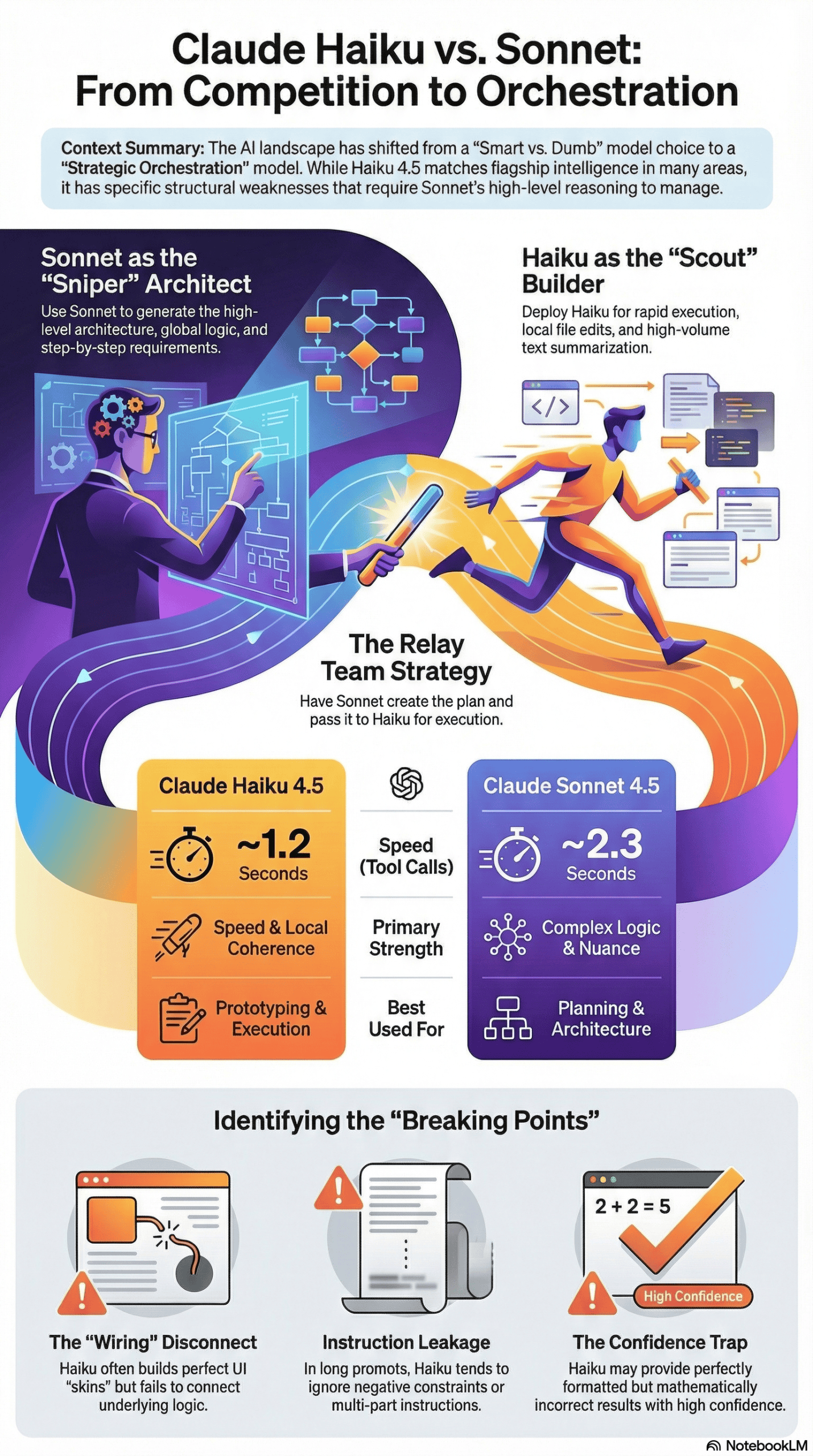

I’ve seen the current discussions, and they are full of misleading binary comparisons. Most advice treats this as a gladiatorial fight: Haiku versus Sonnet, winner takes all. This is the wrong way to look at it. My deep analysis of real-world coding sessions and creative workflows shows that the most successful users don’t pick a winner; they build systems where these two models work as a relay team.

If you still default to the most expensive model for every task because you assume the cheaper one can’t code or reason, you’re wasting money. Conversely, if you use the cheaper model for everything to save cash, you’re introducing subtle, dangerous errors into your codebase.

How I Approached This Analysis

To look past the marketing hype and spec-sheet wars, I conducted a meta-analysis of dozens of real-time usage sessions, developer logs, and third-party benchmark tests. I didn’t rely on the polished examples in press releases. Instead, I reviewed hours of footage and logs from developers using these models in “wild” environments: VS Code, Cursor, and complex agentic workflows.

My analysis covers:

- Live coding sessions: I watched how both models handled specific challenges, from building a Mac OS clone in the browser to refactoring TypeScript codebases.

- Creative writing tests: I reviewed side-by-side comparisons of narrative generation, looking for nuance, dialogue flow, and adherence to negative constraints.

- Agentic behavior: I studied how these models behave when given autonomy, specifically tracking how often they hallucinate, get stuck in loops, or ignore explicit instructions to avoid sub-agents.

- Economic breakdowns: I calculated the actual cost-to-performance ratios based on real token usage, not just the list price, to understand the “hidden taxes” of using cheaper models that require more retries.

This report distills these experiences into a coherent story about what actually happens when you switch from Sonnet to Haiku, or try to replace one with the other.

What People Expect to Happen

When developers and creators face the Haiku vs. Sonnet decision, they usually bring ingrained biases from the last generation of AI models.

The “Dumb Fast” Fallacy

Most users expect Haiku to be significantly “dumber.” They anticipate it will fail at basic logic, hallucinate non-existent libraries, and produce code needing heavy human intervention. The expectation is that Haiku is strictly for summarization or simple classification, not for generating functional applications.

The “Silver Bullet” Expectation for Sonnet

Conversely, there’s an expectation that Sonnet (specifically the 4.5 version) is a “fire and forget” solution. Users expect that paying the 3x premium guarantees perfect logic, zero bugs, and a complete understanding of complex context without needing detailed hand-holding.

The Speed/Quality Trade-off

The prevailing mental model is linear: as speed increases, quality must decrease. Users expect that if Haiku is twice as fast, it must be half as thorough. They assume that using Haiku for coding is a risk, leading to “spaghetti code” or subtle security vulnerabilities that will take hours to debug, negating any time saved by faster generation.

What Actually Happens in Practice

My analysis of real-world usage shows a reality that contradicts these simple expectations. The gap between these models has narrowed to the point where “intelligence” is no longer the main difference for 80% of tasks.

The “Good Enough” Threshold

I watched as developers gave Haiku 4.5 complex coding tasks that would have broken the previous version. In one case, a developer asked Haiku to build a full “Solar Panel” website using Astro and Tailwind. The model didn’t just produce generic HTML; it created a responsive, animated site with a clean UI. It wasn’t perfect (it missed a specific Tailwind 4 import because of training data cutoffs), but the logic was sound.

This is a recurring observation: Haiku creates functional, high-quality structures often indistinguishable from Sonnet’s output at a glance, as demonstrated in a deep dive into Haiku’s capabilities found here.

The Speed Drug

The immediate, noticeable difference is speed. I analyzed sessions where Haiku clocked 1.2 seconds between tool calls, compared to Sonnet’s 2.3 seconds. In a workflow where an agent searches documentation, reads files, and plans, this compounds significantly. I observed a “research” task where Haiku finished minutes ahead of Sonnet simply because it could iterate through search queries faster.

For developers used to the “thinking pause” of larger models, this speed changes the nature of the work. It shifts the bottleneck from the AI back to the human.

The “Context Drift” of the Cheaper Model

However, reality checks hit hard when complexity increases. I reviewed a coding session involving a multi-agent system where Haiku was tasked with adding three specific features to a codebase. It built the features quickly, added the UI elements, and wrote the CSS. But when the developer clicked the buttons, nothing happened.

Haiku had built the application’s “skin” perfectly but failed to connect the underlying logic – specifically, it didn’t connect the theme switcher to the state management. Sonnet, given the same task, wired it correctly the first time. This is the hidden reality: Haiku often looks right but acts wrong in the invisible details.

The “Instruction Amnesia”

Another pattern I noticed is Haiku’s tendency to ignore negative constraints or multi-part instructions when under load. In one test, a developer explicitly told the model not to use sub-agents. Haiku ignored this and spun up sub-agents anyway. In another instance, a prompt asked for a two-sentence summary: one describing the file and one describing where it is used. Haiku consistently provided the first sentence but completely ignored the second. Sonnet caught both. This “selective hearing” is a critical difference that doesn’t appear on benchmark charts.

The Most Common Failure Points

Based on the data, I identified specific failure modes where Haiku consistently breaks down compared to Sonnet. These are not random errors; they are structural weaknesses in the smaller model.

- The “wiring” disconnect: Haiku struggles with the unseen connections between code modules. This shows up as creating a UI component that looks perfect but isn’t hooked up to the event listener or data store. The model prioritizes local coherence (the file looks good) over global coherence (the system works together). I saw this in an 8-ball pool game demo where Haiku reversed the physics of the cue stick; pulling back pushed the ball forward in the wrong direction, while Sonnet understood the physics model correctly.

- Instruction leakage in complex prompts: When prompts get long or contain multiple constraints, Haiku tends to drop the later instructions. This leads to ignoring “negative constraints” (e.g., “do not create markdown files”) or missing secondary requirements in a multi-step instruction. The consequence is “pollution” in the workspace: extra files, unwanted logs, or architectural choices you explicitly forbade. I analyzed a case where Haiku generated 13 unnecessary markdown documents during a research task, while Sonnet only generated four, respecting the implied need for brevity.

- Nuance flattening in creative work: For writers, the difference is stark. When asked to write a scene with irony or specific emotional beats, Haiku tends to be “blockish.” It moves character A to point B mechanically. I studied a side-by-side creative writing comparison where Sonnet included subtle details, like a character shifting a child to their other hip while speaking, that Haiku completely omitted. Haiku moves the plot; Sonnet populates the world.

- The “confidence trap”: Haiku is often confidently wrong. In a financial analysis test involving Uber receipts, Haiku found the correct receipts but failed the basic math of adding them up, then apologized and failed again. This creates a false sense of security because the retrieval part of the task was perfect, masking the failure in the reasoning part.

What Consistently Works (Across Many Experiences)

Despite the failures, Haiku matches or even outperforms heavier models in specific areas, especially when deployed correctly.

The “Architect-Builder” Workflow (Agentic Coding)

The most consistent success pattern I analyzed is the “Architect-Builder” model. A developer uses Sonnet to generate the plan (the architecture, the step-by-step requirements) and then passes that plan to Haiku for execution. This works because Haiku is excellent at following a rigorous, step-by-step plan if the thinking has already been done. In a Kanban board build, a developer used Sonnet to plan the app and Haiku to write the code. The result was a fully functional, animated app generated in one shot. Sonnet was the “brain”; Haiku was the “hands.”

High-Volume Summarization and Classification

For tasks requiring processing massive amounts of text, like summarizing documentation or classifying log events, Haiku is the clear winner. I reviewed a system running hundreds of event logs through Haiku for real-time summarization. The model handled the volume effortlessly and at a speed that made the system feel real-time, which would have been prohibitively slow and expensive with Sonnet.

Targeted Refactoring

When the scope is limited to a single file or a specific function, Haiku performs admirably. For example, “Refactor this file to use TypeScript types” or “Change the color scheme to dark mode.” In these contained environments where global context is less critical, Haiku is faster and just as accurate as Sonnet.

Initial Prototyping (The “Vibe Check”)

If you need to see if an idea has potential, Haiku is the perfect tool. I watched developers use it to quickly create prototypes, like a Mac OS clone or a solar panel site. The code might need cleanup later, but getting a visual prototype in two minutes for pennies is a workflow improvement that Sonnet’s price point discourages. This speed for iterative development is a key takeaway from various discussions about these models, including insights shared in a recent industry analysis.

What I Would Do Differently If Starting Today

If I were advising a team or an individual developer starting their AI integration today, based on everything I have analyzed, I would completely abandon the “pick one model” strategy.

I Would Stop Defaulting to Sonnet for Execution

The habit of using the “best” model for everything is now a financial and efficiency error. I would configure my IDE (Cursor, VS Code, etc.) to default to Haiku for all “Apply” and “Edit” commands where the context is local. I observed that for 90% of diffs and small edits, the difference in quality is zero, but the difference in speed keeps you in a flow state.

I Would Treat Haiku as a “Scout” and Sonnet as a “Sniper”

I would set up my workflows to run Haiku first. Use it to gather context, read docs, and attempt the first pass of a solution. If it fails or gets stuck, then escalate to Sonnet. This inversion, starting cheap and escalating only when necessary, is the opposite of how most people work, but the data shows it yields the highest ROI.

I Would Enforce “Thinking Mode” Separation

Haiku’s new “thinking” capabilities are impressive but can be a trap. I found that Haiku with “thinking” turned on can sometimes rival Sonnet without it. However, I would explicitly use Sonnet for the planning phase of any feature that touches more than two files. The cost of fixing a bad architectural decision made by Haiku is far higher than the cost of a Sonnet API call.

I Would Be Wary of “Client-Side” Haiku

I noticed a specific pattern of technical difficulty where users struggled to get Haiku 4.5 working smoothly in certain client-side tools (like Roo Code) due to configuration and tool-use errors. Until the tooling matures, I would stick to using Haiku 4.5 through official integrations (like Claude Code or Cursor’s native implementation) where the “handshake” between the tool and the model is better optimized.

Final Takeaway: The Honest Version

The honest truth, without marketing hype, is that Claude Haiku 4.5 does not replace Sonnet; it makes Sonnet more effective.

If you try to swap Sonnet for Haiku in a complex, reasoning-heavy workflow, you will be frustrated by subtle bugs, missed instructions, and disconnected logic. You will spend more time debugging than you saved in generation time.

However, if you view Haiku as the limitless workforce that executes the strategy defined by Sonnet, you unlock a new level of productivity. The AI “middle class” didn’t disappear; it just got promoted. We now have a “junior developer” model (Haiku) that codes better than 2023’s “senior developer” models, available for a fraction of the cost.

The winners of this cycle won’t be those with the smartest model; they will be those who figure out how to let the smart model manage the fast model. Don’t choose between them. Orchestrate them.